Disclaimer: This document is published as an academic work. It does not explicity reflect the personal views of the author and instead should be used as reference for the study of ethics and political philosophy.

Illustration of the classic trolley problem. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Illustration of the classic trolley problem. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Author: Alex Neiman

First published: Winter 2022

Course: PHIL 231, Dr. Brian Looper

Institution: California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo

When discussing the theory of ethical decision making known as utilitarianism, one particular ethical dilemma is often discussed. According to utilitarian theory, the dilemma is not a dilemma at all; it has a clear answer. However, this answer seems blatantly wrong to many students of philosophy, and it is on these grounds that they reject the notion of utilitarianism. Such an argument relies on the faculty of intuition to reach an answer, and for this reason, the tendencies of human nature make utilitarian principles appear morally wrong. After investigating human intuition, however, it is evident that it should not be relied upon to answer ethical questions, and that the dilemma in question is not sufficient evidence to dismiss the theory of utilitarianism.

On utilitarianism

Let us establish a complete definition for the theory of utilitarianism as described by John Stuart Mill. The pretenses are that absolute morality exists and that there must be a way to describe it philosophically. Utilitarianism states that a particular action is considered morally good if it produces maximal happiness. Specifically, when someone is faced with a choice of actions, the morally correct option is the one that maximizes happiness. Note that happiness is taken in a broad sense as the summative amount of happiness within all of humanity–not as the happiness of the person committing the act. The time at which the resultant happiness comes into effect does not affect its merit. Given that happiness and unhappiness are inverses, maximizing happiness is the same as minimizing unhappiness. When given a choice between two actions that would cause harm, Mill would claim the morally correct option to be the one that causes the least unhappiness.

Portrait of John Stuart Mill, widely considered to be a founding father of utilitarian philosophy. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of John Stuart Mill, widely considered to be a founding father of utilitarian philosophy. Source: Wikimedia Commons

This theory of utilitarianism relies on happiness being the ultimate good. Mill argues that happiness is the summom bonum, or the ultimate good, and that happiness itself is desired for its own sake. All other intrinsic goods, Mill says, are components of happiness, and therefore contribute towards it. For any action to satisfy the ultimate good, it must work to maximize happiness. When faced with a decision that would either benefit the doer of an act or benefit a random person the same amount, Mill would claim that the choice is not important.

A common objection to utilitarianism is that it would not be practical to act ethically. Those who wish to be morally righteous would need to thoroughly calculate the complete effects of every action, which would be an impossible task. Only an omniscient being could do so. Mill’s answer states that we rely on the generational accumulation of knowledge (Mill 23). We typically follow a set of standard societal rules that forbid us from killing, lying, and stealing. These rules exist as a framework for guiding human behavior, and they are easy to remember and follow. Mill says that they are derivations of the master theory of utilitarianism; in other words, they exist because they typically promote actions which would cause maximal happiness. They are the result of many civilizations’ worth of attempts to promote the supreme good.

Utilitarian investigation of a classical ethical dilemma

Let us now discuss the previously mentioned ethical dilemma–one of the most convincing arguments against utilitarianism–the trolley problem. Suppose you are standing above a railway line on a bridge watching a train pass. There is a crew of workers on the tracks, unaware of the train. They will certainly die if the train continues to travel. Standing with you on the bridge is a fat person. Their heft would be sufficient to halt the train and save the workers. You are presented with a choice. You may take no action and watch the workers die. You may also push the fat person off the bridge, killing them, and saving the workers. According to the theory of utilitarianism, the morally correct action would be the action that would maximize overall happiness. Suppose that the life of each person in the scenario is equally valuable and that their death would bring about the same amount of unhappiness. In this case, the correct choice would be to push the fat person off the bridge–killing them–and saving the others. You would have preserved the greatest amount of life and maintained the greatest amount of happiness.

To most people, pushing the fat person off the bridge would be an egregious wrong. How can utilitarianism be correct to say that it is the moral thing to do? Such an argument appears to stem from intuition. One might argue that that we ought to rely on intuition, not a logical theory, to make such a moral judgement, and that the theory of utilitarianism is wrong. Although such a view seems convincing, it is important to remember that their view relies completely on human instinct.

Analysis

How can one characterize such instinctual decision making? One could reference the societal culmination of knowledge proposed by Mill. Again, he suggests that the rules we generate as a species are learned and passed down. While this is true, Mill neglects to account for an additional consideration: human instinct. The rules humans tend to follow are a combination of learned knowledge and instinct. I am operating several logical conditions concerning instinct. Firstly, animals advance through the process of evolution. A species will introduce and modify its Secondly, humans are highly sophisticated animals to which the rules of evolution apply. Charles Darwin suggests that animals evolve following the “survival of the fittest” principle. In general, the evolution of a species will promote traits which maximize overall survival. As a species evolves, traits that promote survival will become prominent, and traits that reduce survival will diminish. Our instinctual preferences, then, will move us to act in ways that promote the overall survival of our species, not the overall happiness.

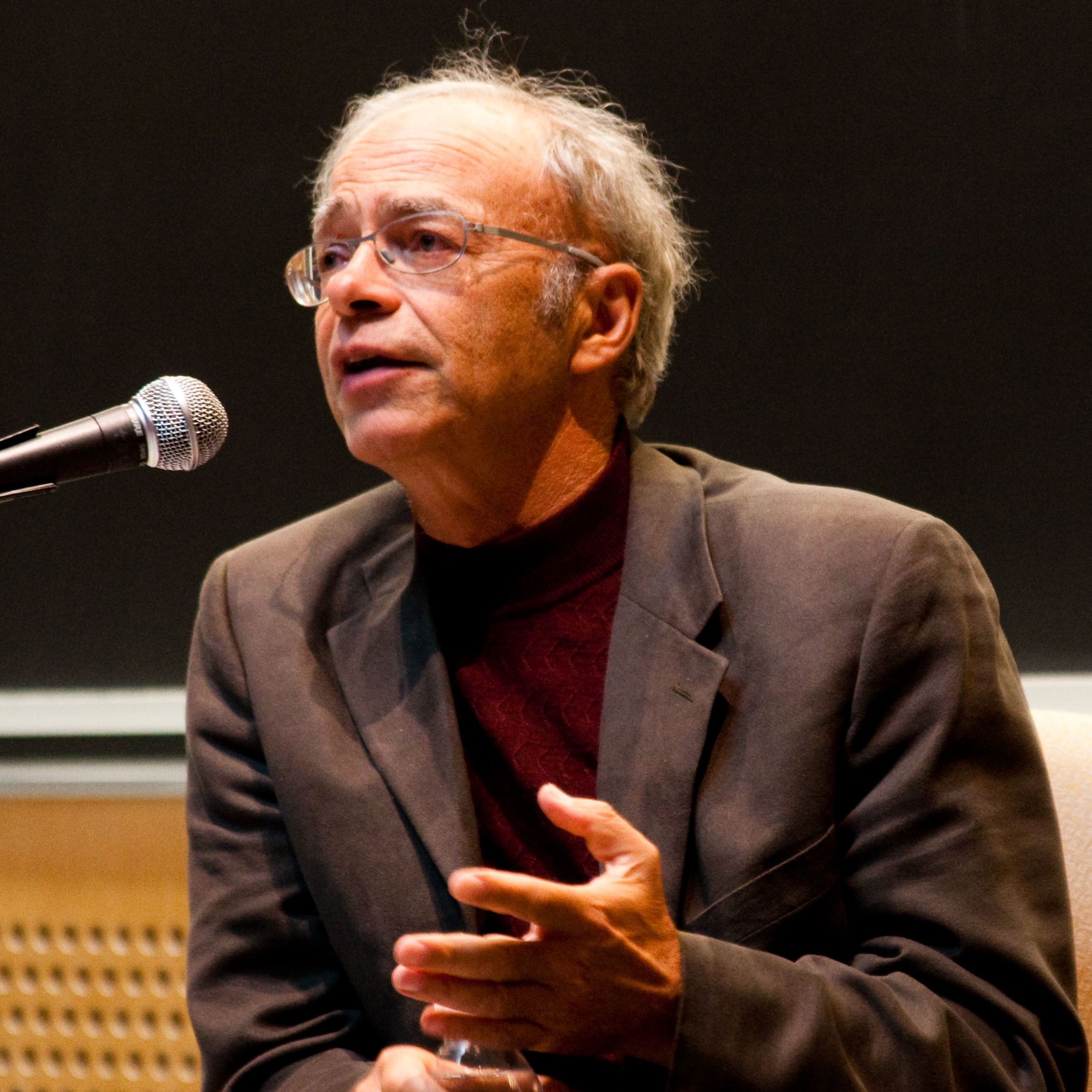

Peter Singer, pictured here, approaches philosophy from a secular utilitarian perspective and has published works concerning poverty, morality, and animal welfare. Source: Wikimedia commons.

Peter Singer, pictured here, approaches philosophy from a secular utilitarian perspective and has published works concerning poverty, morality, and animal welfare. Source: Wikimedia commons.

Human instinct also seems to take over in situations when we either have little time to consider a solution or are in imminent danger of death (the death of yourself or another member of the species). These are not things that we learn generationally; they are ingrained in every human being. Children do not need to be told not to jump from cliffs, for example, because fear of falling is instinctual. Imagine I ask you to jump off a tall cliff. No doubt you would reject my suggestion, not on the grounds of reason, but on instinct. Suppose instead I ask you to jump out of an airplane with a parachute, where you would have no risk of death. Many people still would prefer not to throw themselves out of a plane, even with the guarantee of survival. Only a select few people would enjoy doing the latter, again, on the grounds of instinct.

At first glance, suggesting that instinct leads our decision making seems to conflict with the theory of utilitarianism. A Darwinist may suggest that the only reason why humans truly value happiness is that it is beneficial to our survival. That seems to place survival as the ultimate goal, not happiness. While this may be true, it is important to remember that the principle of utilitarianism is founded on the maximization of human happiness, not human survival.

It is now evident that we cannot use the trolley problem to disprove utilitarianism if we are citing instinct or feeling as the basis for the answer. Humans will rely on instinct to answer ethical problems to which there is no clear solution (such as the trolley problem), but our instinct operates with the intent to maximize human survival. Therefore, acting to maximize human survival has no basis in morality, and human instinct should not be used to distinguish right from wrong. If we grant that statement to be true, then using intuition or feeling to argue against pushing the fat person in the trolley problem is not enough to disprove the theory of utilitarianism. The only reason why we struggle to accept the utilitarian answer to the trolley problem is because our human intuition (in this case, our refusal to kill another human) tells us that it is wrong to do so. As Hume suggests, human decision making is highly influenced by reason, but ultimately relies on sentiment to make the final call. We can consider intuition to be the guiding force of sentiment in the trolley problem.

Alternate perspectives

An objector might claim intuition is not the cause of our rejection of the trolley problem. If it is true that our intuition guides us to maximize the survival of the human species, then the action that would maximize survival would be to kill the fat person and save the five workers. I claim that our intuition tells us to do the opposite. Therefore, the objector would say that my claim of intuition guiding the decision-making process in the trolley problem is incorrect. To defend the argument, I will make an additional claim about human intuition. On the whole, an imminent threat poses a greater risk to our survival than an opportunity for good. Therefore, our intuition has a greater aversion to harm than an inclination towards good. Additionally, our intuition is more sensitive to direct consequences than indirect consequences. Consider the cliff example again. When standing over the edge, we would be gripped by the fear of imminent harm. We would not feel the same kind of fear when the risk of harm is just as present but not as obvious. An example would be standing in a machine shop where harmful chemical fumes are present. In the trolley problem, we have a natural aversion to pushing the fat person because doing so would cause direct harm to another human. Therefore, we will prefer the choice of indirect harm over direct harm.

Another objector may raise an issue with the basis of my argument to begin with. My argument is contingent on the existence of evolution. Those who do not believe in evolution will claim my entire argument to be unsound. I believe that the principle that we have animalistic instincts is self-evident; we can still recognize the tendency of instinct to protect human life2. Therefore, one does not have to accept the entirety of evolution to agree with the argument. Additionally, there are other reasons to believe that happiness is not what motivates instinct. Consider Plato’s explanation of what happens in our dreams. We commit acts that are highly depraved that we would never consider doing in real life. This suggests that humans have an emotional or instinctual side that is motivated by something that is not chiefly concerned with right and wrong. Therefore, we still cannot rely on instinct to tell us right from wrong, and the trolley problem still cannot be used to disprove the theory of utilitarianism.

Works Cited

Darwin, Charles. On the Origin of Species. 1859.

Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism. Hackett Publishing, 1863.

Plato. Republic. 375.

Hume, David. Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals. 1751.

Footnotes

- However, if one holds the belief that humans are somehow above animals and do not have such a sense of instinct, then at that point my argument can no longer be defended.